-

Identify the nonuseful response: when do people react badly to me? What was I doing at the time? How did I sound, how did I feel? I zero in on the non-useful response by exploring what was going on outwards and inwards when it happened.

-

Internal inquiry: I look at what’s going on inside me when those events occur, when similar events occur, and what I remember from before I started the inquiry. This gives me insight into what, in me, contributes to the negative reactions in others.

-

Get perspective: discuss it with friends, check my assumptions, try to find out if I’m overreacting (gee, that never happens!), look for an outside point of view on specific incidents. I do this after the internal inquiry, so I have time to brace myself for unpleasant truths. Sometimes it’s other people; sometimes it’s me. Quite often it’s both, but I only control one end of that.

-

Identify the underlying problem: this is when it starts getting easy. Having faced the unpleasant reality that the world can’t read my mind and might not think well of me when I behave less-than-brilliantly, now I just have to notice what the fear or the need was that triggered my unuseful reaction in the first place. There’s usually a fairly easy way to address that, sometimes simply by crediting it.

-

Monitor and reprogram myself: when similar situations arise, I pay attention to the present moment, and react appropriately to that, keeping half an eye on my old reactions so they stay out of the way. It doesn’t take long to reset to the usual defaults of consideration and common courtesy. I’m lucky that way.

Author: Isy

Author: Isy

Posture matters, across species

I lived in a dog-friendly marina. – Trust me, this is relevant.

|

It’s not just about the scenery.

|

I saw dogs in every degree of getting along — or not.

I saw the active posture of dogs who were used to plenty of food and care…

and dogs who clearly weren’t.

This was interesting to me as I was coming out of a period of being thugged on by every force outside myself that had a duty to care for me. Being, not only neglected, but frequently tormented and abused in response to most of my efforts towards survival and care, left me very nervous indeed.

|

| Not good for the brain. Or anything else. |

I was having trouble with my posture, and – limited by impaired kinesthesia (the sense we have of where our body is in space) – I was working out exactly what the trick points were.

– My low back was in a tight sway, sticking my stomach and butt out egregiously. I lost over an inch of height to that sway in my back.

– I recently realized that, when I fall back in this posture, my abdominal muscles are braced outward. I’m not slack in the belly; the muscles are braced for an incoming blow!

– My neck was hunched against my shoulders. This was funny because I did used to have a bit of a weightlifter’s neck, short and thick; but that was many years ago… when I lifted weights.

– My tailbone was curled in tight, which I only realized after my physiotherapist at the time taught me to straighten it out as a way of releasing tension on the nerve “sleeve.”

– The points of my shoulders were rotated inward. I attributed this to an effort to ease the nerve opening through my shoulders, but that doesn’t actually make sense.

All of these things reduced effective nerve flow to my limbs, shortened the wrong muscles, limited blood flow to where I needed it most, and reduced my capacity for physical exercise.

|

| And you can see how happy it makes me! |

Since activity is key to managing CRPS and keeping the autonomic nervous system under some kind of regulation, this is actually a huge problem.

Good posture is not about vanity, it’s about feeling better, being stronger, hurting less, and surviving tolerably well.

Watching all those dogs running around and deciding whether to let others sniff their butts,

|

| You’re not imagining things: the pit bull is missing a leg. |

I realized exactly what my posture looked like: a dog in a hostile area, not wanting to fight, but protecting its spine while bracing for blows. Always ready to snap into action. Never knowing when things will go sour, but pretty sure they soon will.

That’s what those years had brought me to. It was a reasonable response, but not useful.

|

| This is what’s really going on when I fall back into that posture. |

I’ve managed to explain this “braced dog” image to my current physiotherapist, who’s wonderfully willing to work with my rather original views. He comes up with ways to tell my body how to stand/sit/move like a calm, alert animal, instead of one that’s braced for the next fight…

|

| I can’t do anything about the 3 extra cup sizes this endocrine dysregulation caused, but my back and shoulders hurt less anyway. |

And I remind my too-nervous nervous system that a calm dog can snap into a fight about as fast, but tends to find far fewer of them.

In the meantime, relaxed animals have a lot more fun.

Postscript on self-imaging

Nearly every time I see pictures of someone in regard to posture or movement explanations, it’s someone really fit.

Now, really. Is that who needs to know?

Much as I loathe looking at myself from the outside, using my own image here is preferable to the implicit lie of using others’ figures. So here I am, warts (so to speak) and all.

|

| /shrug/ Could be worse. |

Waiting

It’s always a bit of a circus. As I said to the lab tech, “I used to be a trauma nurse. What would be the fun of being an easy stick?”

This time, I had the joyful opportunity of having the first lab tech assess my veins and go find a better vampire without even poking me first. His hands were actually shaking by the time he left.

All I could do was laugh to myself. I used to have hosepipes for veins. They were still leathery, full of valves, and inclined to roll, but with a sharp needle and good technique, you could nail ’em with your eyes closed.

Now it takes 5 minutes with the warm pack (hot water in a blue glove) and the sharpest needler in the house. She got it in one.

In thematically related news… I’ve been essentially incommunicado since I moved into the new cabin. Internet is supposed to come tomorrow and AT&T has knocked $50 off my bill for not providing service yet and having terrible communication with me (losing notes, calling back the wrong week, trying to send me on wild goose chases) when they do get through.

Every effort to do anything other than nest — carefully, gently, and in small controlled increments of effort — seems to take 10 times the effort it should. Not two or three times. 10 times.

All I can do is laugh to myself… and, when necessary (such as when someone’s looming over me with a sharp instrument and a purposeful expression), sitting firmly on my perpetually hair-triggered fight-or-flight response.

As I said to the same skillful lab tech, “I have good doctors, and I’m finally getting lab tests, PT and good care.”

This is why I protect my mental faculties so vigilantly. They let me assess the real risk, the real effort, the real impact of the moment, so I can talk the CRPS-triggered responses down out of the sky.

And then wait for my system to recover.

I think I’m ready to go now.

Pain rating scales that describe reality

I got to the usual 1-10 pain rating scale and my gorge rose. That’s so irrelevant to my life now that I can’t even throw a dart at it.

Between my self-care strategies and spectacular mental gymnastics, the level of what most people would experience as “pain” is a secret even from me, until it’s strong enough to blast through the equivalent of 14 steel doors, each three inches thick. At that point, the numeric level is off the charts.

What’s useful and relevant is how well I can cope with the backpressure caused by the pain reflexes and the central and peripheral nervous system disruption this disease causes.

You can read on without fear, because for one thing, it’s not contagious, and for another, your experience of pain — whether you have CRPS or not — is uniquely your own. This is mine, as it has changed over the years…

Step 1: Acute CRPS, with otherwise normal responses

My first pain rating scale, just a few years into the disease’s progress, was suitable for a normal person’s experience. My experience of pain was still pretty normal (apart from the fact that it didn’t know when to stop):

|

Mental impact

|

Physical changes

|

|

0

|

|

|

No pain at all.

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

Hurts when I stop and look.

|

|

|

3

|

3

|

|

Neither looking for it nor distracted.

|

|

|

5

|

5

|

|

Noticeable when concentrating on something else.

|

Nausea, headache, appetite loss.

|

|

7

|

7

|

|

Interferes with concentration.

|

Drop things, grip unreliable.

|

|

8

|

8

|

|

Difficult to think about anything else.

|

Trouble picking things up.

|

|

9

|

9

|

|

Makes concentration impossible.

|

Interferes with breathing pattern. No grip.

|

|

10

|

|

|

Can’t think, can’t speak, can’t draw full breath, tears start – or any 3 of these 4.

|

|

|

Unrated even numbersindicate a worse level of pain than prior odd number, which does not yet meet the criteria of the following odd number. Note that weakness is only loosely related to pain. I drop things and have trouble picking things up at times when I have little or no pain. However, as pain worsens, physical function consistently deteriorates.

|

|

Notice how the scale ties the rating numerals to physical and mental function. This is crucial, for two reasons — one personal and one practical:

– Personally, I can’t bear to let misery get the better of me for long. Tying the numbers to specific features keeps the awful emotional experience of pain from overwhelming me. Making the numbers practical makes the pain less dramatic.

– Practically, in the US, health care is funded by a complex system of insurance. Insurance companies are profit-driven entities who are motivated not to pay. They don’t pay for pain as such, only for limits on function. This makes my pain scales excellent documentation to support getting care paid for, because MY numbers are tied to explicit levels of function. (Hah! Wiggle out of that, you bottom-feeders.)

Step 2: Early chronic CRPS, with altered responses

My next was upwardly adjusted to describe learning to live with a higher level of baseline pain and noticeable alterations in ability:

|

Mental impact

|

Physical changes

|

|

3

|

3

|

|

Neither looking for it nor distracted. Forget new names & faces instantly.

|

Cool to touch @ main points (RCN both, dorsal R wrist, ventral L wrist). Hyperesthesia noticeable. .

|

|

5

|

5

|

|

Interferes with concentration. Anxiety levels rise. Can’t retain new info. Can’t follow directions past step 4. May forget known names.

|

Nausea, headache, appetite loss. Grip unreliable. Hyperesthesia pronounced. Color changes noticeable.

|

|

7

|

7

|

|

Absent-minded. White haze in vision. Can’t build much on existing info. Can follow 1 step, maybe 2. May forget friends’ names.

|

Drop things. Cold to touch, often clammy. Arms & palms hurt to touch.

|

|

8

|

8

|

|

Speech slows. No focus. Behavior off-key. Can’t follow step 1 without prompting.

|

Can’t pick things up; use two hands for glass/bottle of water.

|

|

9

|

9

|

|

Makes concentration impossible. Hard to perceive and respond to outer world.

|

Interferes with breathing pattern. No grip. Everything hurts.

|

|

10

|

|

|

Can’t think, can’t speak, can’t stand up, can’t draw full breath, tears start – or any 3 of these.

|

|

Notice how specific I am about what general tasks I can complete — following instructions, lifting things. These are the fundamental tasks of life, and how do-able they are is a fairly precise description of practical impairments.

Step 3: Established chronic CRPS

And my third changed to describe living with more widespread pain, a higher level of disability, and — most tellingly — a physical experience of life that’s definitely no longer normal:

|

Mental impact

|

Physical changes

|

|

3

|

3

|

|

Neither looking for it nor distracted. Forget new names & faces instantly.

|

Cool to touch @ main points (RCN both, dorsal R wrist, ventral L wrist, lower outer L leg/ankle, R foot, B toes). Hyper/hypoesthesia. Swelling.

|

|

5

|

5

|

|

Interferes with concentration. Anxiety levels rise. Can’t retain new info. Can’t follow directions past step 4. May forget known names.

|

Nausea, headache, appetite loss. Grip unreliable. Hyper/hypoesthesia & swelling pronounced. Color changes. Must move L leg.

|

|

7

|

7

|

|

Absent-minded. White haze in vision. Can’t build on existing info. Can follow 1 step, maybe 2. May forget friends’ names.

|

Drop things. Knees buckle on steps or uphill. Cold to touch, often clammy. Shoulders, arms & hands, most of back, L hip and leg, B feet, all hurt to touch. L foot, B toes dark.

|

|

8

|

8

|

|

Speech slows. No focus. Behavior off-key. Can’t follow step 1 without prompting.

|

Can’t pick things up; use two hands for glass/bottle of water. No stairs.

|

|

9

|

9

|

|

Makes concentration impossible. Hard to perceive and respond to outer world.

|

Interferes with breathing pattern. No grip. No standing. Everything hurts.

|

|

10

|

|

|

Can’t think, can’t speak, can’t stand up, can’t draw full breath, tears start – or any 3 of these.

|

|

The CRPS Grading Scale

The other scales measure the wrong things now. Asking me about my pain level is bogus. It would have the asker in a fetal position, mindless; is that a 5 or a 10? Does it matter?

I need to avoid thinking about depressing things like my pain and my disability. I focus pretty relentlessly on coping with them and squeeezing as much of life into the cracks as possible — on functioning beyond or in spite of these limitations.

The fourth rating scale is much simpler than its predecessors. It’s based, not on level of pain or disability, but on the degree to which I can compensate for the disability and cope past the pain. Therefore, this rating scale remains meaningful, because it describes my actual experience of life.

|

Mental impact

|

Physical changes

|

|

A. Coping gracefully

|

(baseline)

|

|

Track to completion, baseline memory aids sufficient, comprehend primary science, think laterally, mood is managed, manner friendly.

|

Relatively good strength and stamina, able to grasp and carry reliably, knees and hips act normal, nausea absent to minimal, pulse mostly regular.

|

|

B. Coping roughly

|

B

|

|

Completion unrealistic, extra memory aids required and still don’t do it all, comprehend simple directions (to 3-4 steps), think simply with self-care as central concern, unstable mood, manner from prim to edgy to irritable.

|

Moderate strength and stamina, grip unreliable and muscles weaker, balance goes in and out, knees and hips unreliable, nausea and blood sugar instability alter type and frequency of intake, occasional multifocal PVCs (wrong heartbeats) and mild chest discomfort.

|

|

C. Not coping well

|

C

|

|

Hear constant screaming in my head, see white haze over everything, likely to forget what was just said, focus on getting through each moment until level improves, manner from absorbed to flat to strange, will snap if pushed.

|

Muscle-flops, poor fine and gross motor coordination, major joints react stiffly and awkwardly, restless because it’s hard to get comfortable, unstable blood sugar requires eating q2h, bouts of irregularly irregular heartbeat.

|

|

D. Nonfuntional

|

D

|

|

Unable to process interactions with others, suicidal ideation.

|

Unable either to rest or be active. No position is bearable for long.

|

There is no Grade F. Did you notice that? As long as I have a pulse, there is no F, which stands for Failure.

In the words of that divine immortal, Barrie Rosen, “Suicide is failure. Everything else is just tactics.”

So what’s the point of all this?

Documenting our own experience in terms that are meaningful and appropriate advances the science. The treatment for this disease is stuck in the last century in many ways, but that’s partly because it’s so hard to make sense of it. The better we track our experience with it, the better outsiders can make sense of it.

Since studies, and the funding for them, come from those who don’t have the disease, this is the least — and yet most important — thing that we can do to improve the situation for ourselves and those who come after us.

This isn’t a bad snapshot of the natural history of my case, either. Understanding the natural history of a disease is a key element of understanding the disease. Imagine if we all kept pain rating scales, and pooled them over the years. What a bitingly clear picture would emerge.

I’ve never sat back and looked at all of these pain rating scales together. It’s certainly an interesting mental journey.

Important legal note: These forms are available free and without practical usage limitations; to use, alter, and distribute; by individuals and institutions; as long as you provide free access to them and don’t try to claim the IP yourself or prevent others from using it. All my material is protected under the Creative Commons license indicated at the foot of the page, but for these pain scales, I’m saying that you don’t have to credit me — if you need them, just use them.

Bien approveche: may it do you good.

Only one thing at a time

Yesterday, I got rich red dust from lovely Mt. Konokti (pronounced kon-OCK-tye) all over my car, the last of my stuff out of storage, and a lovely home cooked dinner. (J is an excellent cook of wholesome homey fare.)

This morning, the dust was washed off, all fluid levels checked, dog kisses washed off the insides of the windows, and a cooler packed with ice and three days of food (the time it’ll be until I can use a kitchen.)

J’s invisible presence is with me in the carefully packed, wholesome food, the shiny purring car, and periodic calls where he reminds me to be alert at rest stops and be sure to call his brother as soon as I get moved in.

I’m in a stunning pain flare, with both CRPS and fibromyalgia getting well into gear, but I made it to the halfway mark and the motel’s spa is being warmed up — just for me.

The coming week is booked with appointments for 3 different types of therapy and 3 different specialist physicians, for a total of 5 initial assessments and tests in 4 days. “Gruelling” doesn’t come close.

Somewhere among those appointments, I’m moving to the place nearest to the doctors that I could possibly afford and probably survive. Unfortunately, it’s right up the mountains — all covered in snow.

Snow.

I can’t say any more about that.

It would be all too easy to get wound up about this… let’s call it, madcap adventure of a week. But I’ve had enough of “wound up,” I really have. (There’s a post cooking in my head about what it’s like to live with a fight-or-flight system that’s physically hardwired into gear, and a heart that isn’t interested in that much strain. I don’t recommend it.)

I’m thinking of this as simply a series of tasks. One thing happens after another, and only one thing can happen at a time.

J says that often: “One thing at a time.” He’s a bit hyper too, and these are words he has had to learn to live by.

This way, I don’t have to think of the whole fraught mass of deadlines and how many times I have to drag my wretched carcass down into town regardless of what it could do to me. I just think of the next task.

Pretty soon, that’s going to be a hot-tub in the middle of a green field next to a state park.

Lets face it, there are worse things.

Departure

It’s my last evening in what has begun to feel like home. You should see the prep on the garden. Some fabulous food will come out of there. Pretty much all J’s work of course, but I cheered.

Long drive for two days, then ill be in (gulp) the snow. Considering the latitude it shouldn’t last long.

What really unnerves me is four solid days of physical and mental assessments. It’ll be an interesting week. I’m pretty sure I’ll make it to the weekend….

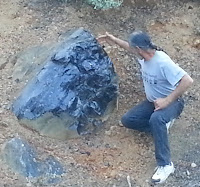

Obsidian drive

We took a walk in the creek where we admired treasure troves of river-rubbed obsidian, much of it the size of a fist, some rather larger. We got really excited about some of the larger stones, grapefruit-sized.

Only ones that fit in a pocket followed us home:

Then, as it was Sunday, we decided to go to church. For us, this involves no pastors, but maybe pastures…

We went up and around new roads, over beautiful hills, along streams, through forests… and found the sources of all that obsidian.

Great bands of fat black glass sloped up through orange, yellow, white earth.

Some of it spilled onto the edges of the road, much of it clinging to the rockfaces.

Chunks the size of heads, boulders the size of steamer trunks. J remarked, “We hit the motherlode, baby, we hit the motherlode!”

I was so scamperingly excited to get pictures and samples that J was both cracking up and worrying slightly. When I was preparing to dash down a narrow stretch of road to get a shot, h e didn’t send me on and wait by the car… he grabbed my hand and led the way, saying, “If we’re going to get hit by a drunk driver, we’re going to get hit together. Come on, baby, let’s go.”

He met a carnivorous specimen which tried to bite off his finger when, trying to give me a more interesting shot, he reached out to touch it:

This piece has been hacked at by amateur geologists trying, and failing, to collect that enormous sample — well, trophy. J was just being friendly, but the edges are just as glassy-sharp as if he had had more hostile intentions.

It made our river-rubbed fist- and grapefruit-sized pieces look very small indeed — and very gentle!

The temperature dropped suddenly, 3 degrees in 2 minutes and falling. I turned from the rockface and took this picture of the lush region above the volcanic bed just as it did so:

J chased me into the car and ignored all my mindless “ooh, ooh!” noises and frantic pointing after that.

He has seen me, in a 70 degree (Fahrenheit) room, bundled up in a huge sweater and shaking with autonomic chill. When he knows what to look out for, he does a better job of taking care of me than I do. “If I had to drag you by the hair, I was gonna get you off that mountain. By your heel, your ass, whatever. It was getting too damn cold.”

I have to say, it feels good to have backup. I don’t take it for granted.

According to some theories, all this glorious obsidian might have something to do with why this one area of NoCal does not feel like it’s festering… but I’ll let the classical physicists, quantum physicists, wiccans and shamans argue about that. I’m just soaking up the joy of living practically on top of a fat pile of one of the coolest rocks in the world.

"Angel" in my mouth

One word I never used, because it was just too hokey, was “angel.”

Yes, I used “sweet pea” with perfect ease, but couldn’t bring myself to call anyone “angel” with a straight face.

What can I say? We all have our limits, however idiosyncratic.

I thought, What an overused, overfluffy, overly silly word to use about someone who is decidedly human — as everyone I’ve met so far is.

Then I went through the Years from Hell, a period of about 3 years I try not to even think about because it was so bloody harrowing it’s unbearable to remember, and there’s nothing to be done now to change that.

One set of surprises were some of the people who I was sure would come through, but fell from view when their actions were supposed to match their words.

Many people who seem awfully nice are more socially adept than genuinely good. It’s an important distinction.

Starting late 2011, I found myself using the word “angel” as an endearment for a very particular set of people. It came naturally to my mouth as a substitute for “sweetie” or “sweet pea” when speaking to those who showed up when the going became almost impossible,

who never gave up on me despite good reason to do so,

and who showed up for me through thick and thicker.

The handful of people who made the key difference between my living and dying, are the ones I call “angel” — and find it easy to do so.

It’s not over- anything. It barely does them justice. And, I have to say, some of them were a real surprise: people who aren’t apparently nice can be genuinely decent and deeply good.

Like every ER nurse ever, I used to preen myself on how good a judge of character I was. This disease, and the many versions of Hell that it comes with, teaches us a thing or two about human nature.

It’s fair to say that, even at my most brain-frozen, my judgement about people’s core attributes is better than it used to be.

I know where to find the real angels on this earth.

|

| Among my besties, that’s where. |

Pushing back on neuroplasticity

-

from the first refusal to cut pain signals off…

-

to the growth of the brain cortex area that monitors that body part, so it can handle more pain signals and provide less space for normal body areas…

-

to the deeper remapping and rewiring that alters cognition, disrupts memory formation, screws up autonomic signalling, knocks endocrine and digestive function out of whack…

-

and so forth.

It’s important to stay on top of the brain, so to speak.

Having said that, it’s not completely reciprocal, nor is it ever under perfect control — unlike a good trapeze act.

- neurons hook up, and a connection (or association) is made;

- if the connection gets used (or the association is allowed to stand), more neurons hook up to make it stronger;

- once enough neurons have hooked up, the connection becomes like a good road;

- and the thing about good roads is, they get used, even if they’re used for something odd.

- Make sure the roads in your brain are useful to you.

- Do that by pruning the connections you don’t want.

- Prune those connections by letting the associations die.

- Let a connection die by deciding to think about, or do, something else, whenever it comes up.

Consistently. Persistently. Relentlessly. - And keep making that decision every time it comes up.

It works by a negative, which is not how we are taught to do things: turn away from the response, shut out the perception, ignore the link. That’s how you prune an unhealthy connection.

It takes time, but it works. The time will pass anyway, so your brain might as well be better off at the end of it…

|

| Only constructive connections, please. |

|

| Egrets make great distraction, especially in funny socks. |