I wrote the start of this for a fellow spoonie today and realized it’s a good starting point for a subject most people find overwhelming: reading medical science when you’re starting off as a non-scientist.

The article I cite first is a good example to start with, because it’s written well and has passages of clear English to work with. So…

Here’s a science article which describes immunoglobulin E pretty thoroughly: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541058/

I suggest reading the abstract and introduction. After that, just skim the first sentence of each paragraph, since (in science writing) that tells you what the paragraph is about.

If the first sentence makes no sense, skip that paragraph.

If you can figure out the first sentence, glance at the rest of the paragraph to see if there’s any more to glean. If not, move on..

It’s a skill

Reading science is a skill, and skills take time to master. That’s expected! Share what you glean with your doctor and ask them to help you understand it better.

Honestly — this isn’t to puff myself up, it’s just the nature of patients to dis themselves, so hear me out — if you can read my stuff and make out half of it, you are plenty smart and literate enough to start reading science. It’s just work and time, and the time will pass whatever we do, and the work will get easier with time. We just have to take care of ourselves and pick our time, when we’re chronically ill.

Using the right amount of honey

Doctors might give you attitude about comparing your Google search to their medical degree, but that’s not what you’re doing: you’re studying up on your condition, which is wise, and you’re expanding your info base on this thing that has imposed on your life, which is survival.

So, feel free to correct them sweetly, and don’t be afraid to pour some admiration on them if it helps them to re-focus on your information-gap.

The point is not who knows more overall. That’s not in question. When you talk to your doctor, you’re talking to someone who had to memorize, for instance, the Krebs cycle (here’s a partial explanation: https://www.medschoolcoach.com/the-krebs-cycle-mcat-biochemistry/) — so, yes, they have a depth and nuance of knowledge that’s nearly impossible to replicate without going to medical school.

They like having that acknowledged, because they take a lot of painful flak for not knowing everything about everybody’s illnesses all the time, and they need to know that you know what an effort they made to be able to work as a doctor.

So, it’s good to acknowledge that enormous effort.

Then they are usually able to hear you when you clarify that you’re not arguing with them, you’re trying to improve your understanding of this thing that affects you so profoundly. You trust them to help because of their knowledge.

Trust. Help. Knowledge.

These are keywords because they are core professional values for most doctors.

They’re important to acknowledge, and great to invoke and rely on.

That said… if you can’t rely on these characteristics in your doctor, even after you tell them that that’s what you need, then it might be time to find another doctor if you can. These core values are far more important than whether a doctor has good social skills or a good handshake.

When all is said and done, guess who has to live (or not) with the outcomes? It’s you. While the doctor is the subject-matter expert on the medical info around your condition, you are the subject-matter expert on being in your body and dealing with the fallout. There’s a degree of respect that should go both ways, though modern practice makes that hard.

What you need most from your doctor is:

Trustworthiness (intellectual trustworthiness, specifically).

Urge to help.

Knowledge.

Those are the keys to good care.

Mental skills for the non-scientist to start with

The key to reading science is realizing — or at least, going ahead as if — you’re perfectly capable, and just need to practice. Science is written by humans, and you’re a human too.

1. You are a perfectly sensible person. If you’re reading this, you know how to read (or access translations from) English; also, you have access to a whole world of dictionaries. MedlinePlus is especially helpful in explaining concepts and helping us learn to read medical stuff.

2. Not all scientists can write well in English, and none of them write in English all the time. That’s okay. They went to school for a long time to get extra vocabulary and learn to do what they do; good for them. They’re still people, and they have to write in English at least some of the time. That’s where you can come in.

3. You can read the English just fine. Trust yourself and take time. With practice, you can learn more lingo over time, and get better at reading more science.

Just work from what you can understand now, and let that grow over time. You’ve got this.

Choosing credible sources

While you’re learning to read science, start where you can and work from there. As you get more confident and your understanding grows, you’ll learn to be choosier.

The gold standard for science info

When learning how to assess science, you’ll hear a lot about placebo-controlled, double-blind studies and that method is often important. This method of science gives us more reliable statistical probabilities about whether something will work in a certain situation. The statistical probabilities become reliable when several thousand people (“subjects”) have been tested, probably over many different studies.

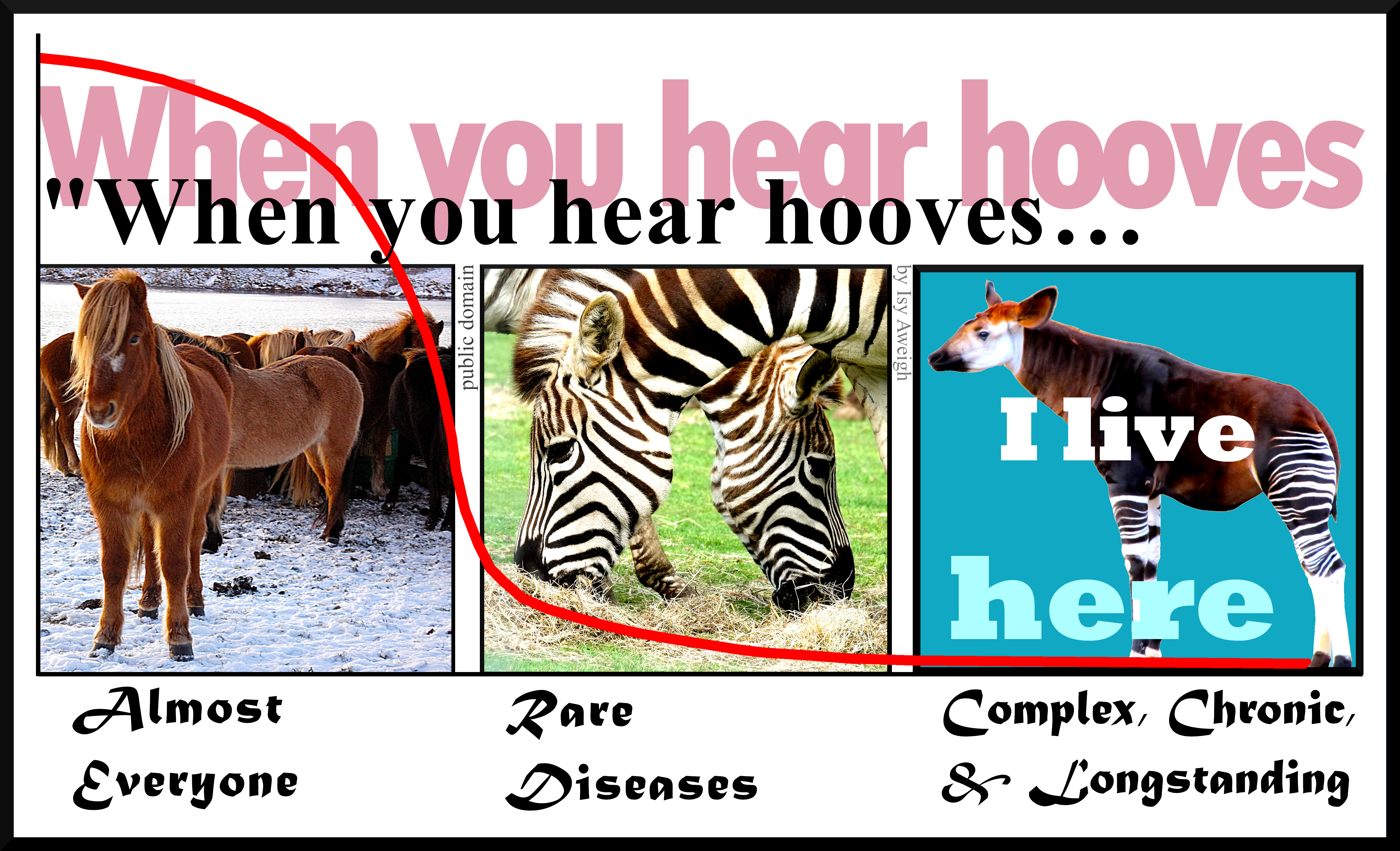

With rare diseases, this is obviously pretty unlikely, so we have to work with less scientific certainty. C’est la vie.

Statistical probabilities have more limited value for patients than doctors, because we’re individuals, not pooled data. There used to be a phrase used in medical school: “Statistics mean nothing in the case of the individual.” This has gone by the wayside a bit, but it’s still true.

We may have to cast our nets further afield, because we’re looking for clues that might help us, personally. Be aware when you’re doing that, and put those science reports in your mental “hmm, maybe” folder.

I showed a case study that had a marvelous impact to one of my best doctors. He said to me, “If I could put that effect in a bottle, I would. It worked for that person, and we have no idea why. We do know that it doesn’t work for all these other people. Everybody’s different. Figuring out how to apply one thing to help a lot of people is our holy grail!” Lloyd Saberski, MD.

And that’s why doctors rely on the pooled data gathered from the scientific method. They want to help as many people as possible with each thing they try. Otherwise they fear they’ll spend too much time chasing rainbows.

We patients have to find our own rainbows, just as we have to count on our doctors to keep an eye on what’s statistically worth trying. It really is teamwork, and we both need to do our jobs.

What’s peer review?

Before you give a study to your doctor, it’s worth checking if it’s from a peer-reviewed journal. Don’t expect them to put too much stock in it otherwise.

Peer review means that other people in related fields have checked it over for sanity and validity. This is important for us patients, as well as the doctors who rely on the information.

You can Google whether the journal your article was first published in is a peer-reviewed journal. JAMA, BMJ, and the Lancet are all reliably peer-reviewed.

The value of literature reviews

Then, after a fair amount of studies have been done on a topic, there’s usually a literature review. This is when a qualified scientist takes a close look at all the studies, throws out the ones that were badly designed or poorly run (because bad technique creates bad data. “Garbage in, garbage out”) and writes an overview of what the current good science says.

They also discuss the strengths and weaknesses in the data, and suggest where future science funding could go, in light of the science so far.

Literature reviews are wonderful places to improve your knowledge of your disease/condition, expand your vocabulary, and get a lot better at understanding what goes into the science on your condition in the first place.

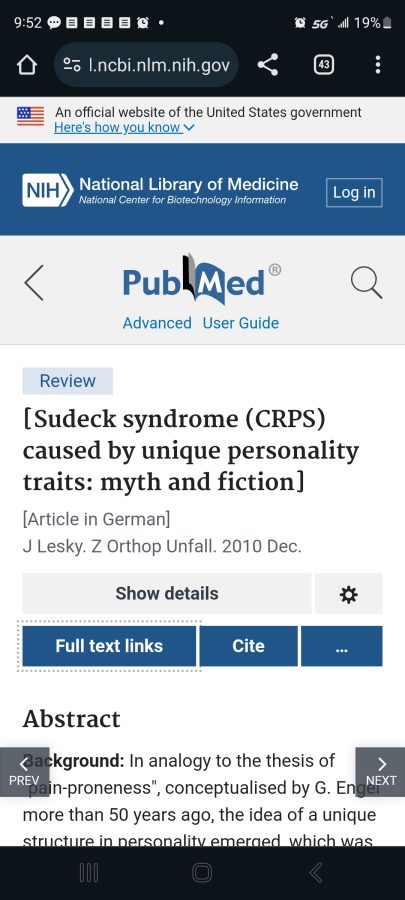

For instance, it used to be widely believed that most people with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome had had traumatic childhoods. (“Blame the parents” LOL.) There was a literature review done on about 30 years’ worth of studies, and it turned out that almost all of them were so badly-designed, poorly run, and calculated with so much bias, that nearly all of the studies had to be thrown out!

This taught me very important lessons:

– Just because most people say it, doesn’t mean it’s right, even if they should know better. This is an excellent attitude to have while reading science.

– Methods matter. You’ll learn over time how to sense whether the methods used are appropriate to the topic studied. The wrong method can lead to truly bogus results. The method has to fit the material.

– People lose their minds when they think about pain, as well as when they think about childhood trauma. In practical terms, this means I have to approach all normal (non-CRPS) people’s reasoning about my condition (which is characterized by relentless agony which a non-CRPS’d brain cannot even conceive of) with compassionate criticism. They do not know what it’s like, nor how to live with that pain and still think rationally. They’re not able to know. I don’t want them in a position where they do know, because that’ll mean their lives are as battered as mine is.

Therefore, every word they say has to be filtered through my awareness of how their minds get lit up by unreason, when they think about my pain. This, believe it or not, is perfectly natural. (Look up “amygdala hijack” for background on this mechanism.)

I survive because I’ve learned to substantially displace or ignore one of the most powerful primitive signals in the human body. That isn’t natural, and nor should it be.

These scientists mean well, without question. However, their logic is necessarily fractured when thinking about this, because they lack my tools for facing it. I need to dig into their data and methods before I can buy into their conclusions.

That’s good to know!

The conclusion of that literature review? CRPSers are likely (not guaranteed) to have had relatively eventful lives. Whether the events were traumatic or wonderful wasn’t relevant to our probability of developing CRPS.

In other words, we live in interesting times!

Where to find science to read

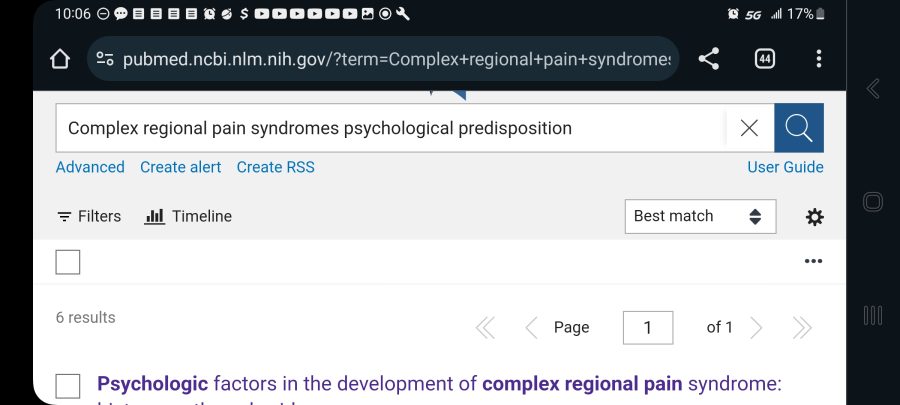

Google pubmed, and you’ll find the National Library of Medicine (NLM) division of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This is a searchable science library which hosts articles from all around the world, in whatever language they were published in plus English. You can search any valid medical term — for instance, use the full name of your disease rather than its initials, for better results:

Some of them have full articles that are free to read (look for “Full Text Link”) …

…But most will show only the abstract, that is, the high-level overview of what the study is about. For our purposes, that’s the most important thing, so it gives you something useful to work with.

The interface gives you options for saving, sending, and citing the articles.

To use these, just touch or click the one you want. They do exactly what they say they will.

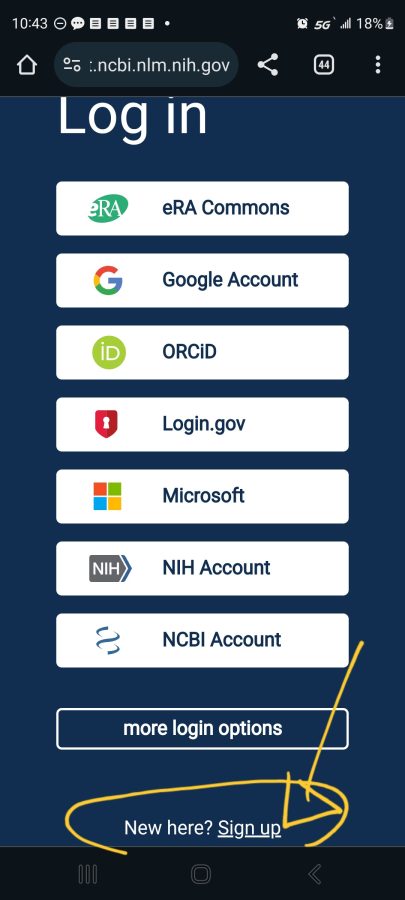

If you touch one of the menu options that requires them to store the info on their side — like “Collections”, “Bibiography”, or “Citation Manager”– it will give you what you need to sign in (if you already have an account) and, at the very bottom, the option to “Sign up”:

The site is very helpful; just slow down and let yourself look at one thing at a time.

Once you feel more self-assured, try out Google Scholar. It’s smaller in some fields and generally less selective, but that can be good. I suggest saving it for later only because it’s got fewer guard-rails. We’re all different, though, and you might find that easier.

These two libraries aren’t identical. They do overlap.

A word about MeSH terms

MeSH stands for Medical Subject Heading. It’s a curated list of specific terms used in the National Institutes of Health materials. This kind of consistency is necessary when organizing a stupendous medical database like the National Library of Medicine.

MeSH terms are listed at the bottom of each article. If that article was useful, you can click the MeSH terms to have them saved to your PubMed search history:

Here’s a tip: when using their Search tool, don’t worry about capitalization, but be very particular about spaces and punctuation. Copy them exactly.

Using MeSH terms will improve your future searches, because it makes the most of the databases self-referencing mechanisms.

Trust your eyebrows

Best tool in your mental toolbox: when you’re reading sentences you know you do understand and, yet, you feel your eyebrows moving around on your forehead… that logic is not right.

The scientist might be misinformed, biased, pulling a fast one, or just plain wrong, but it doesn’t really matter which — that logic is not right. The underlying pattern-matching part of your brain can tell. That’s a primitive part of the brain and, when you’re paying attention to it, it’s extremely hard to fool!

Trust your eyebrows. If you want to, save the article and come back to it when you know more, so you can figure out where the problem is. I assure you, there is one. Your eyebrows don’t lie.

Feed your brain

Reading science is hard work and brains are big hungry things at the best of times. Feeding it right can be a huge help.

Meds & caffeine

If you’ve got attention problems, adjust your meds and caffeine to give you some extra focus when you’re reading science. It’s a lot more fun that way!

Smart produce

Green, blue, and purple foods are absolutely marvelous for brains — and pain. They feed the nerves, literally. I know you needed an excuse to eat more blackberries, blueberries, collard greens, and rocket salad, aw shucks.

I also know it’s not the cheapest stuff in the market. Explore your local options for farmer’s markets, roadside stands, produce sales, and organized assistance like EBT/food stamps and healthy-living programs giving more access to produce in the state, like they have in Massachusetts and California and other places.

This is a great opportunity to learn more about your condition and to bring what you’ve learned into your life (more on that later), and the upfront effort pays off so much in the end.

Body-safe phenylalanine

Obviously, if you’re prone to phenylketonuria, skip this part! IYK,YK.

Also, keep in mind that this can have an effect on some meds — sometimes giving them a boost, sometimes making things worse. Be sensible, do your due diligence, and study it up for yourself if you’re interested. Also, use your self-documentation skills: note what you do and what it does to you, change what needs to change, and take responsibility for the results of your choices. We are our own best caregivers.

I’m discussing the physiological activity of this thing with the weird name, and what I’ve found in my life and those closest to me. This isn’t any kind of assurance that it’ll do good for anyone else. Put it no further than “hmm, maybe” in your mental filing system and do your own further research to validate what I say and get an idea how it might work for you, yourself.

Basically, phenylalanine is a precursor to the “up” side of the neurotransmitter suite, dopamine and norepinephrine and even epinephrine (they all transform into each other as needed). These neurotransmitters carry messages among the parts of the brain involved in learning and memory. Taking in phenylalanine can have a truly astonishing effect on attention and memory WHEN you’ve got fundamental deficits, as do people with central and longstanding pain and some other conditions.

TL;DR — If it doesn’t make an obvious difference in less than an hour, you don’t need it.

I’ve trialed using aspartame, which went well for me. (Discussing my results with my doctor paved the way to including SNRIs in my med regime, to my considerable benefit.)

Food sources of phenylalanine

This is where hard cheese and smoked or processed meat shine. They’re rich natural sources of phenylalanine. They also have saturated fats which, in moderate doses, seem to help with pain and brain symptoms.

As a moderate part of a well-balanced diet, folks.

This hasn’t been well-studied; it’s one of those things you pick up after being involved with self-managed patients for over 30 years.

It doesn’t take much. I found that 2 or 3 bites of aged cheddar would absolutely light up my brain for 45 min to an hour and a half, depending on my deficit.

One pal of mine keeps meat jerky sticks on hand for study sessions. Aged cheese works better for me; jerky works better for them.

Now, unfortunately, mast cell activation problems have moved cheese and smoked meat out of my diet. When I need a brain boost, and it feels like cheese might help, I have to use a supplement instead.

Supplementing phenylalanine

It’s more measurable to use a supplement called DLPA, or d,l phenylalanine. It’s a blend of natural and manufactured forms of phenylalanine. One works better for pain and another for depression, but the blend seems well-tolerated and helps both. Phenylalanine suppresses certain inflammatory kinases and may help suppress pain at the spinal root (that is, right where the base of the peripheral nerve path comes out of the spine) as well as helping with mentation and cognition. (Sarcastic Sister notes: The recent science about it magically disappeared in the wake of the “war on pain meds” and I won’t pretend to understand why.)

There is a maximum recommended dose before it gets toxic, but if you’re seriously thinking about that, you’ll want to do your own studying, and might want to talk to your doctor about SNRI meds as a possibility. (The N is for norepinephrine, which phenylalanine supports.)

Why bother with learning how to read science?

Knowledge and understanding are the most powerful tools you can have for dealing with complex chronic health problems. It may or may not change what you have to deal with, but it certainly gives you more and wiser options about how to deal with it.

Even if you aren’t ready to start now, you can circle back around to this whenever you want. It’s attainable; you can do it. It’ll always be there (although individual articles and topics may come and go.)

The patients who learn the most and put that to work in their own lives, are the patients who most consistently beat the odds and have the best quality of life over time.

Therefore, better information leads to better living with complex chronic illness. My HIV patients taught me that 32 years ago at my first nursing job, and it’s truer than ever now.

Note: Nobody here says it’s easy. That said, our complex chronically ill lives are never easy.

Pretending that getting through the day is not, itself, almost a superhuman task is a disservice to our strength, so let’s just start off by recognizing that everything we do is really hard work.

Knowing that, I have found that the effort of learning and applying what we learn pays off a whole lot more than passively waiting to be saved and feeling rotten all the while — and still being wrecked & exhausted.

I can whole-heartedly recommend learning and figuring things out. It’s a winner.