Ted Mancuso is famous for his enthusiastic Renaissance mind and the kinds of explanations it leads to. If that kind of thing doesn’t drive you up a tree, it’s enormously rewarding, because it can pay off for years.

It may not be immediately obvious how Chinese calligraphy, the evolution of the yin/yang symbol, James Joyce’s “The Dubliners”, a great general who died 2 thousand years ago, and the spinal root of a nerve, all relate to each other — let alone to the logic of a single move in t’ai chi.

For him, they do.

Moreover, when he explains it, it makes perfect sense.

Compared to his ferally free discursiveness, my mind is almost tame. It helps me relax into training, because I don’t have to struggle with my own lateral-mindedness and force it into literal-mindedness — I can just say what I think and get instant yes/no/kinda, from a teacher who gets it. As I said to his wife once, “I LOVE that man.”

There’s a lot to think about in t’ai chi chuan, the way it’s taught at Ted’s academy. For that reason — and here I apologize to my fellow ADD-ers — this is a long piece, because I have to circle through a few related ideas to get to the point in a meaningful way.

One thing that’s becoming very clear to me is that, ideally, there is no such thing as an inattentive moment or an inactive body part. Even a part that’s held still, is still alive, still alert, still awake to the world and present in the mind.

Ideally.

Introducing Peng (however you spell it)

The concept of “peng” leads us closer to understanding this. If your native language is a Chinese language or French, your pronunciation is fine or nearly fine. If it’s not, you’re in trouble.

The word is pronounced with a very hard P and an English A that clearly came from the upper crust in the south of England. Its pronunciation is closest to “bong” in English, but, as a resident of a medical-marijuana state, I can’t write “bong” without inviting confusion, and as a longtime pain patient, I can’t write “pang” for much the same reason.

So, hard P, haughty A, and in here I’ll spell it pæng.

Pæng is often explained as a defensive or guarding force, but that’s an oversimplification. Ideally, pæng never leaves, except when displaced by a more specifically directed action.

Pæng makes directed action a lot faster, too, because of the way it creates potential space in any direction, which is then easy for you to fill. Much more efficient than the usual wind-up we usually find ourselves doing before initiating a directed action.

(This Marx Brothers compilation is hypnotic, to the point of being kinda creepy. If you’re triggered by casual violence, skip it.)

Pæng is the force you use to define the space you inhabit. Since you’re always in your own space, it makes sense to maintain pæng. Pæng is the ground state of each limb “at rest” (a relative term.)

Ideally.

This is what we work towards, anyway.

A relevant discussion of expertise

I’ve noticed, for much of my life, how the true experts in any movement (martial arts, dancing, rock climbing, surgery) don’t get in their own way. This is a lot easier said than done.

There’s a reason why true excellence is generally pegged at 10 years of experience. I figure it takes a couple of years to learn what’s supposed to happen, and then it takes most of the rest of the time to unlearn the reflexes that get in the way of achieving that. That’s my theory. Unlearning is that hard.

We lack faith in ourselves, at a subtle level, and it creates the interferences of hesitation, fidgets, and engaging the wrong efforts, then having to disengage them and reassess, then go forward again, in a sort of ongoing, half-unconscious dance towards accomplishing the goal.

Ted says that people come to his classes hoping to come in as they are and go straight on to excellence, and have to come to terms with the need to back up to roughly when they learned to walk/run really well and go on from there.

It’s part of his particular genius that he doesn’t try to get each person to unlearn their ways, he simply creates what he calls a shadow posture, and I call a parallel posture (though we mean the same thing), so that class time and practice time are spent in this new and evolving structure that creates the foundation for excellence to be built on. It’s up to you whether you go into that space the rest of the time, but it’s pretty hard to resist, because it’s delightful.

That very delightfulness is unnerving. I’ve had to integrate a lot to be able to accept something so alien to my experience of the last 14… no, actually, 40-odd years. It’s just so foreign, so antipathetic to what I have known for so long. Fortunately, I have ways of dealing with that…

My style of learning something profound goes like this:

- I charge in for a bit, throwing myself at it like spaghetti at the wall.

- Then, when my body-mind has reached a saturation point of new information and everything inside is sitting up and screaming, “WTH??”, I sit back for awhile to rethink and mull the new ideas involved in these skills.

- I feel and learn how they filter down and across and through every applicable aspect of life, and I have to semi-consciously work to let those old assumptions shift, evolve, and change.

- Then, when my mind has reached a saturation point of digested information, I can move back into activity, usually with a significant bump up to a new level.

Winter is a good time to digest, and with the waxing days I’m getting impatient and ready to bump up. I’m thorough, and I give full credit to my subconscious processes and the importance of mental digestion. When it comes to my learning style, I’m fairly relaxed…

We’re not relaxed in our tasks until we’re expert. I wonder if we can accelerate towards expertness by learning to relax in our tasks. There’s an empowering thought.

Expert surgeons have far better outcomes, partly because their lack of irrelevant motion means that they leave less trauma behind. Their scalpels don’t make any pointless cuts, their hands don’t jostle any irrelevant flesh, there simply isn’t anything done under the skin that isn’t directed towards the goal. There is not a wasted motion, and not a wasted moment.

They don’t dither; they do, and they do it decisively and cleanly. If something turns out a bit different from what they expect, they go with it — no holding back, no denial, just accept, redirect, and move on. They don’t interfere with themselves, and thus they don’t interfere with the work.

The truly expert surgeon, a few of which I’ve been privileged to see, is a breathing artwork of purposeful action and focused intent.

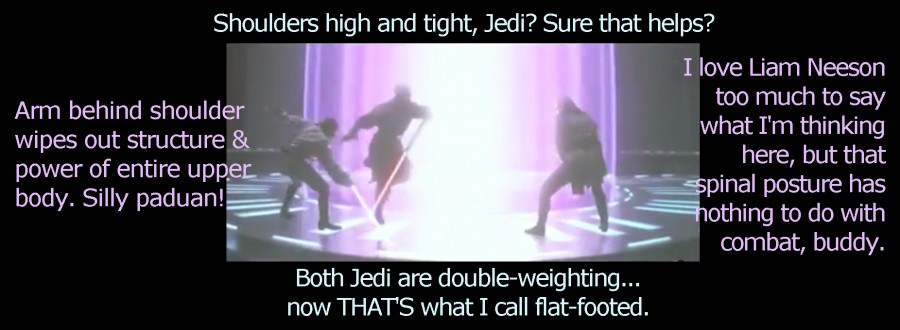

Martial arts is a bit more accessible to most people, so let me show you a popular and priceless example of an expert martial artist next to a couple of wonderful actors who can’t help getting in their own way. Here is the famous fight scene between Darth Maul and the two heroic Jedi, Qui Gon and a young Obi-Wan Kenobi:

All rights to this film belong to 20th Century Fox, in case someone forgets.

I included the whole fight scene. (You’re welcome, Marie P. and Steven R.) If you’re impatient, skip to the last 2 minutes. You’ll notice that the only reason the bad guy lost was a moment of inattention. He moves with effortless elegance, decisiveness, and power, while the Jedi are fighting their own bodies with every move, hulking their shoulders and flexing like mad. It looks exhausting! It took a lot of Lucasfilm to spin the contest out past the first minute, the imbalance of skill is so great.

Darth Maul is relaxed. It makes him effective. Qui Gon and Obi-Wan are not. They’re braced and clunky, utterly without pæng.

All right, given that this force (as it were) of pæng both protects space and creates space, what the heck is it, exactly?

Very simple. Not easy, but simple.

Pæng is the yielding resistance of a tree branch or a length of spring steel, or, for that matter, of a good dancer’s arms.

You push one part of the branch, and the whole bough may sway, but its balance is undisturbed. You push your good dance partner’s hand, but that doesn’t just move her hand — her whole frame absorbs and responds to your push with a graceful springy motion and she rotates, balanced over her own feet, as far as your push goes (backwards and in high heels, most likely. Be impressed.)

That is the force called pæng.

Let’s return to the tree branch for a moment. It allows us to extend the analogy without special training.

Take a good look at an oak, maple, or a eucalyptus tree. Look at a branch from its tip to the root of the tree. You can always follow a single, sinuous line from tip to root.

That tree holds the branch up from root to tip, without any muscles at all. It lifts it from underneath its feet, up its trunk, and floats it out into space from there. This is how the force flows. Not muscular at all, but very, very strong. It’s pure physics.

The tree also holds the branch outward with curves that act as support structures (like the curvilinear welts in plastic packaging, to keep the package from being flattened), in order to make the most of the space.

Bounce a branch lightly. Observe the change in the movement. It bounces more near the point of impact, and as the springiness absorbs the motion, it moves less the closer it gets to the spine. I mean trunk. Did I say spine? I meant trunk. Of the tree. In this case.

This calm-but-alive springiness, this resistance without strain, lifting up from the root through the trunk, opening without pushing, pressing without squeezing, all at the same time, is pæng: the whole branch, from trunk to leaftip, is awake all the time, ready to play with the wind all the time, ready to soak up the raindrops all the time, connected through the trunk or stem to its root all the time. Every touch on the way is received and understood, and responded to naturally. It is always alive with this springy yet relaxed, rooted yet responsive energy.

In humans, pæng can be modulated. This is part of the martial aspect of t’ai chi: intensify pæng to ward off an attack or prepare for one, shift pæng to draw the opponent, release pæng to snap into an attack, but always, always have pæng as your ground state. It gives you a safe, structured space to work from.

Ideally. That’w what we work towards.

Now that we’ve mulled the nature of pæng, we’re a bit closer to understanding what Ted and the t’ai chi chuan classics mean when they use the word “relaxed.” In our extreme-adoring Northern/Western Hemisphere culture, “relaxed” is the opposite of “tensed”, or even “stressed.” A certain floppiness comes to mind, even a resistance to being vertical.

Tense:

[] | | | L

Relaxed (Western style):

8)________|

A “relaxed” body, in this sense, is not ready to move — far from it. It probably wants another drink!

The ancient Chinese traditions cultivate the middle way, not extremes.

As it happens, this is an excellent approach for many people with central nervous system dysfunctions, because our disrupted systems are hardwired to charge wildly between extremes. The more we strengthen our access to the middle ground, the more stable our central nervous systems become, and the better we can get.

Simple. Not easy.

With this in mind, we have to repurpose the word “relaxed” so it’s not a synonym for “floppy”, but a distinctly different term that describes the useful middle ground between “floppy” and “tense.”

Tense: [] Relaxed: 0 Floppy:

| ( | )

| }|{

| / \

L / \ 8)_________|

It’s easy to see, even in these keyboard-figures, which level of energy makes it easiest to move in a useful way, doesn’t it?

How do you want your surgeon to be, heaven forbid you ever need one? How do you want to move when you dance?

Darth Maul seems quite a bit different now, doesn’t he? Actually, he does remind me of a couple of doctors I’ve worked with…

Shortly after I drafted this, Ted saw me struggling through a leg-intensive exercise. He said, with sympathy, “I see why you find these leg exercises so exhausting. Your leg muscles are fighting with each other in every direction.”

I went away and thought it over.

Well, of course they were fighting each other in every direction. This was the setup:

- When I was 10, I got the silly idea that I should have an adult arch to my foot, so I began to supinate.

- That led to my thigh muscles developing lopsidedly, and since I played varsity soccer in high school and ran in my 20’s, they developed lopsidedly a fair bit.

- That led to my kneecaps tracking wrong, and me losing the cartilage under my kneecaps. (I used to think that hurt. Cute!) Ted steered me away from his t’ai chi class in the 1990’s because I was so nervous about my knee pain (really cute!)… so I took his shaolin kung fu class instead.

So, over 15 years later… I’m far too frail for serious kung fu and Ted has become a breathtakingly subtle teacher of t’ai chi; I’ve gone through several rounds of posture training (round 1, round 2, round 3); and, now that the pieces are finally coming together (big clue: if it bears weight, it affects your posture), I’ve been working like mad to rectify my knees.

They still pull to the outside, from the habits laid in by my childhood efforts to lift my arch, and my knees hurt like blazes when they bend. To manage that, I practiced pulling them to the inside, but not directly — kind of rolling my lower thigh muscles inside and upward at the same time… While my habitual muscle pattern pulls outward and up.

Weren’t we just watching Liam Neeson and Ewan Macgregor do something very similar (if a lot more cutely)? Muscles fighting each other in every direction, literally at every turn?

The fighting was simply wrong. …And I don’t mean in the movie.

That’s no way for a body to behave, fighting itself. I don’t want my body to fight itself.

I didn’t see that changing the fighting would work, because there would still be fighting.

Finally, I straightened up. I said to myself, in tones of firm parental authority, “Knee, do it right. I’m not having you fight about it. I’m going to relax — unwind every muscle and make them stand down and wait for orders. You’re going to do it right the first time, because nothing is interfering and nothing is asleep. It is … relaxed.” Pæng.

I lifted my leg and put my foot down. It felt different.

I bent my knee. It was fine, absolutely fine.

I tried the exercise. The thing was completely painless, and floatingly easy.

Buyer beware — it’s a process. For me, the issues are simple, although annoyingly tricky to work with:

- My levels of tension and awareness, not to mention relaxation and attention (those are 4 completely different concepts, you’ll notice), change so much from day to day.

- I still have nearly 40 years of walking habits that I’m building an alternative to.

- I still have to take lip from my knees now and then, which slows me down for recovery, and I have to mentally go down there and tell everyone to stop arguing and let me mend.

It’s a process. However, it’s well begun. It’s all about relaxing, in this special sense of pæng.

It’s like this stuff works …

Love it! I find the relaxedness (new word 😉 ) in Tai Chi more feasible for my body than trying to get myself to relax in Kung Fu sparring, but it’s one of those things which we can totally develop through practice and repetition so I’ll get there hopefully! 😉 Watching Darth Maul again is an education in itself eh? I grabbed my breakfast and got comfortable before pressing ‘play’ and enjoyed the artform 🙂

I’m sooo glad that you’re enjoying the Tai Chi as much as I do, and wow the benefits for everyday life are fantastic! I still find myself raising my shoulders in concentration-tension at the laptop sometimes and it’s Tai Chi that has got me paying attention and knowing how to relax without flopping. Plus the moment I initiate the ‘relax’ command my psyche joins in just like it does in Tai Chi so even at the laptop I get an ‘ahhhhh’ moment. Lovely!

That sense of filling the space, standing tall, yet being relaxed and aware is woooonderful. The more of my day I manage to extend that way of being to, the more calm and beautiful life is to experience. Lovely!

And I know I’m not saying anything much here, just reacting and smiling (and waffling)! Hehe

I’m really enjoying reading your posts sharing your experiences on this journey, xx

You’ve done it again. There’s some kind of cosmic timing going on with your posts and my life. (think Twilight Zone theme song here)

I had given up on supplements in the USA but you inspired me to look again and I may have found an answer, just in time.

After avoiding starch of any kind since 1990, I was lured into eating spelt when I lived in Italy and it just felt wrong and got way worse as time goes on – after years of being accused of neuroses of every kind – now VALIDATED! It feels wonderful to see it written and explained. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.

FYI (just in case): Only recently I found out that if you don’t eat gluten/starch, you’ll have a negative reading on the celiac test. I was again told that I was crazy when a positive result was impossible without eating it daily for at least 2 weeks before the exam. Most doctors don’t even know this.

Thank you so much for explaining complex ideas in a clear manner to challenged patients. I’ve enjoyed your posts for years now and what I’ve learned has helped me immensely in navigating this illness.

I’m so glad to be useful, Colleen 🙂

You’re absolutely right about the test. What it tests is not the *potential* for a reaction, but whether an *existing* reaction has been triggered deeply and long enough to create a significant histological shift.

I didn’t know it took that long, though. I couldn’t take a meaningful test for celiac, because after 2 weeks of daily gluten I’d be babbling, drooling, and bedbound, not to mention bloated to the size of a planetoid.

It’s funny, I had a tickle in my brain –“mention spelt” (in the next post) — the gods must have heard you 😉